My step-dad* has follicular lymphoma that morphed into the more aggressive diffuse b-cell lymphoma. Yesterday he went into hospital for a month long stem cell treatment. There was a 6% chance his cancer mutate. He now has a 30% chance of survival. There’s a 2% chance he’ll never make it out of hospital.

My step-dad* has follicular lymphoma that morphed into the more aggressive diffuse b-cell lymphoma. Yesterday he went into hospital for a month long stem cell treatment. There was a 6% chance his cancer mutate. He now has a 30% chance of survival. There’s a 2% chance he’ll never make it out of hospital.

My mother had breast cancer (that’s her on the left, next to my step-dad). She was lucky. After a full mastectomy on her left side, she went into remission. She is now 8 years cancer free. Some women opt for breast augmentation procedure to feel confident after the surgery.

My father had a stage 4 invasive melanoma removed from his back. They did an x-ray and found shadows on his lungs. He was told he had 3-6 months left to live. They treated him with antibiotics as a precaution, and the shadows on his lungs cleared. It had not metastasised after all. He gets to live.

My step-dad might die of cancer.

I talk to my mother on the phone and she says she’s tired. My step-dad isn’t working. Mum works nightshifts and visits my step-dad in hospital during the day. She wants to take time off work to spend with him, but they can’t afford anymore unpaid leave.

My step-dad is still with us, but there’s always another appointment, another complication, more bad news.

Sometimes I feel sad, but most of the time I’m too busy worrying about my mother to feel anything for myself.

My mother is a nurse and she struggles to manage when she should be a concerned loved one and when she needs to be a medical professional. My step-dad’s kidneys have failed multiple times and, on all of those occasions, it was my mother who saved him, who recognised the symptoms and insisted he go back into hospital.

He doesn’t want to live his life in hospital beds.

He no longer likes the taste of beer.

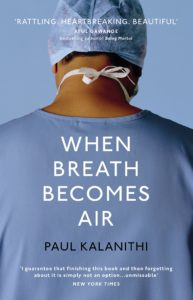

I’ve recommended a book to my mother, something I think will help her work out what to say. Something that will give her permission to be a concerned loved one, and not a nurse.

That book is When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi.

Kalanithi was a neurosurgeon. He was also diagnosed with stage IV metastatic lung cancer. He died before he finished writing the book, and the last few chapters are written by his wife, who survives him. Kalanithi was in his final year of residency as a neurosurgeon and neuroscientist when he was diagnosed.

Kalanithi was a neurosurgeon. He was also diagnosed with stage IV metastatic lung cancer. He died before he finished writing the book, and the last few chapters are written by his wife, who survives him. Kalanithi was in his final year of residency as a neurosurgeon and neuroscientist when he was diagnosed.

My step-dad used to be a bricklayer and a labourer. He now weights 63kg, despite being 6 foot 1. His body had always been strong. It has held him up when he’s been too tired, hungover or too sick to keep going. Now his body is a prison. It is a building on fire and he cannot put it out.

Kalanithi begins his book by talking about patients he’s operated on, by talking about his life. As the book progresses, this line between patient and doctor blurs. When Kalanithi is diagnosed, he is both the patient and the doctor. He expects to consult on himself.

Kalanithi moved to neurosurgery after doing a masters in literature because he wanted to learn what makes life meaningful. While initially wanting to get closer to the line between life and death, Kalanithi was ultimately attracted to the link between illness and identity and how a loss or change of bodily function can completely reshape a person. The irony, I suppose, is that he ends up experiencing this first hand:

“Lucy said she loved my skin just the same, acne and all, but while I knew that our identities derive not just from the brain, I was living its embodied nature. The man who loved hiking, camping, and running, who expressed his love through gigantic hugs, who threw his giggling niece high in the air — that was a man I no longer was. At best, I could aim to be him again.”

Kalanithi’s book is a heartbreaking read because he plans for a future he knows he no longer has. He knows what the diagnosis means. He researches his odds in medical journals. He still makes plans.

This is partly because, as a medical professional, Kalanithi knows how uncertain the odds he’s researched are. He knows that he’s planning his life around educated guesses so, in the absence of certainly, Kalanithi decides to live:

“I began to realize that coming in such close contact with my own mortality had changed both nothing and everything. Before my cancer was diagnosed, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. After the diagnosis, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. But now I knew it acutely. The problem wasn’t really a scientific one. The fact of death is unsettling. Yet there is no other way to live.”

Kalanithi has a child with his wife after his diagnosis. Caddy is 9 months old when he dies. My favourite part of the book where his wife asks “Don’t you think saying goodbye to your child will make your death more painful?” Kalanithi responds: “Wouldn’t it be great if it did?”

I don’t know what it’s like to be diagnosed with cancer. I don’t know what it’s like to have everything you’ve worked towards ripped from you. We define ourselves through time; by what we have done in the time we have. We all think we have an infinite about of time. We have an imagined self who uses that time better than our current self. I do not know what it feels like to lose that future self to cancer.

What is it like to be told you don’t have a future, or worse, that no one knows how much of a future you have?

I hope I’ll never have to know, but not knowing makes supporting my step-dad harder.

How do you support someone with cancer?

This is what I’ve learned from Kalanithi:

You don’t try and take away the pain.

You don’t try and ease their suffering.

You give them something worth suffering for.

The pain Kalanithi feels is the pain of life. It’s the pain of having done something he doesn’t want to lose.

It’s the pain of having lived and having left something behind.

Isn’t that all we really want, after all? To leave something behind that we can be remembered by.

*Technically, they aren’t married, but it has been 10 years.